How do you go from Life Without Parole to Life With Parole to Life?

Can you get it back? Once you’ve been incarcerated, can you get back your life, your ability to make a living, conversations where you don’t have to explain your choices to a Parole Officer, a belief in the people around you, a sound night of sleep, love for your family, a second chance.

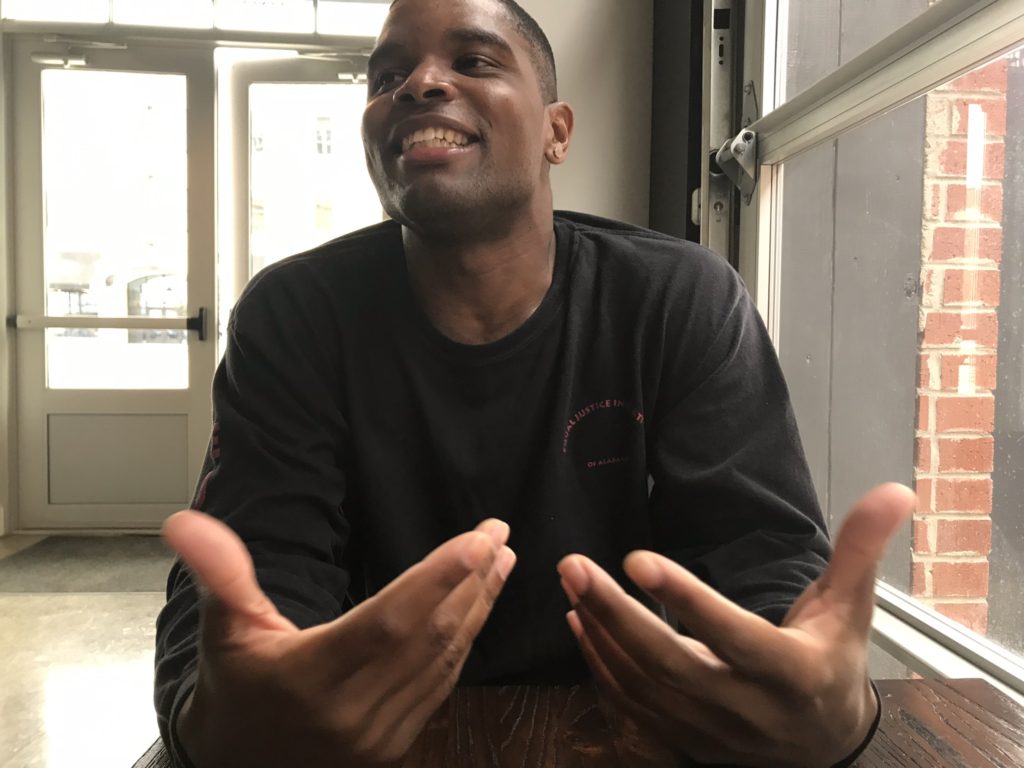

“All of my life, being incarcerated, I was angry. I had stopped believing in people because of my family. They turned their backs on me. Wasn’t nobody there for me but my mama and one of my sisters and I’m the baby of five,” Kuntrell said. “I just stopped believing in people.”

Family is a rub and all too often they rub you the wrong way. I remember something written by Maya Angelou. I know what I just said risks being pretentious, but follow me for a second. Or judge me! Either way, I can take it.

When talking about her mother, Maya Angelou said she was a terrible mother of young children but a wonderful mother for a young woman. They reconnected later in life, after her mother had ducked out. Maybe she was too ambitious. Or maybe she was gay. Or maybe both. But when Maya Angelou was young, her mother took off, chasing after something and leaving behind her little girl.

You might think this would be a deal breaker. You might think she’d never get a shot at redemption, that Maya Angelou would judge her mother’s choices and push her away. But for so many reasons, the thinking of Maya Angelou is earth shattering.

In the case of my family, it’s the opposite. We’re not earth shattering. We’re just plain sad.

My parents were wonderful parents of young children but terrible parents of young men. They’ve been disruptive, meddling in things they didn’t understand but presenting themselves as experts. They’ve been emotional rug pullers, playing games with my stability, and most recently, almost costing me a relationship where I’m happy, where I finally have a sense of home. They’ve been know-it-alls, just ask them – anything – they’ll tell you.

It’s funny when I hear Kuntrell Jackson talk about his family turning their backs on him, I have the opposite reaction of what you’d think, since it makes me jealous. I asked him about parole. “What’s that like?”

“I hate it,” he said. “You know! I got to check in once a month. But I also got to pay $40.00 a month to check in. I hate that. But I understand. Even though I didn’t commit the crime, I was there. I got punished for it. I understand how the system works. The system is always really trying to get you in some type of way. So I’m okay with that because I got my freedom back. I check in once a month. I pay my money once a month. But I don’t like it.”

Who would? I wouldn’t.

I don’t understand how taking $40.00 a month from Kuntrell Jackson, while he’s trying to rebuild his life, helps anyone. He could use the money to pay the gas bill. He could use the money for groceries. He could use the money for a workshop in bookkeeping. He could use the money to go on a date, to pick up the tab, to feel the joy in being able to pick up the tab instead of going splitsease.

“How much longer until you’re done with parole?” I asked.

“I get off in March of 2021,” he said.

This is what we do to antagonize people: we set them free with a caveat. They serve time, they pay their due, but then they’re labeled for life. We take away their freedom, we take away their dignity, we take away their vote and then we expect them to be thankful for a view without walls, without bars.

We’re assholes.

“In two years you’re free,” I said.

“I’m free,” he said.

“You’re free-free,” I said. “Right now you’re free but you’re not free-free.”

“You’re correct,” he said.

I wasn’t playing games. Or maybe I was playing games. There’s something uncomfortable about talking to someone who’s been incarcerated. You’re trying to come across like you understand. But you don’t.

How can you? Really?

So from time to time, to take the edge off, you end up joking around about something that’s anything but funny. I asked Kuntrell if it made him uncomfortable when I was staring at him in the Legacy Museum, when I had a hunch he wasn’t just some random guy standing up against the wall, when I had a hunch he was Kuntrell Jackson, the guy I’d read about in a book.

“You had saw the video and there was some lady who was saying something about the guy in the video is here! And it was like, I just appeared to you cuz when I saw you it was like you saw me at the same time and you was just staring. So I was looking at you cuz you was looking at me and I’m like, I gotta watch him.”

Kuntrell Jackson was 14 years old when he was arrested. 17 years old when he was sentenced to life without parole. 16 years later, when Kuntrell was 33 years old, he was released. It’s tempting to say he was freed. But he’s not there yet. He’s not free, not entirely. Part of it has to do with meeting his Parole Officer once a month, part of it has to do with dropping $40.00 and part of it is noticing people watching him the way you’re constantly on alert when you’re incarcerated.

How do you turn it off? Can you turn it off? Is it a super-power or a disposition which will forever separate Kuntrell Jackson from the rest of us who never had to sleep with one eye open, literally.

“If you do a week in prison, you’re institutionalized,” Kuntrell began. “So I did sixteen and a half years in prison. The thing about prison is your awareness becomes keen. So keen to where I noticed you watching me like that. That’s because if you’re not aware, it can cost you your life. You can mess around and be killed. The same thing with sleeping. You cannot sleep hard in prison because you will get killed in your sleep so every little noise you got to be up! Alert! Always! This everyday in prison.”

Before I met Kuntrell Jackson, I read about him in a book.

“Just Mercy” is a beautiful book. Getting through it takes work since it’s not fiction and there isn’t a river of narrative to float along on like there is in “To Kill A Mockingbird.” I don’t want to compare books, since it’s impossible to justify a preference unless you’re a paid liar on FOX, CNN or MSNBC.

Having said that, “Just Mercy” is a better book in reality since the main character, Walter McMillian, doesn’t die in prison like Tom Robinson. But we needed Tom Robinson to die. We needed to be overwhelmed by the injustice. So what I’m saying is thank God for fiction.

If the controlling idea in “To Kill A Mockingbird” is that you cannot know the world you’re living in until you see it through the eyes of someone else, then the controlling idea of “Just Mercy” is that you are more than the worst thing you have ever done. When I say controlling idea, I mean the big idea. When I say the big idea, I mean the book knocked me on my ass and I can feel the morality of my consciousness resetting. It’s uncomfortable like root canal but necessary unless I want to wander the earth with the stank-ass-breath of a know-it-all.

What’s the opposite of a know-it-all? A broken person.

By the end of “Just Mercy,” the book’s author, Bryan Stevenson admits that he’s a broken person. How can this be? He’s a Harvard educated lawyer. He started The Equal Justice Initiative. He built The Legacy Museum. He shared the stage with Dave Chappelle and Colin Kaepernick to receive the prestigious W.E.B. Du Bois Award. And yet, he asked himself why, over and over, he keeps defending broken people.

When he relinquished the control of presenting like everything is okay beneath the veneer of accomplishments, not only did I get a glimpse of someone I admire, but I got a glimpse of myself. Turns out, in one way or another, if we’re honest about it, we’re all broken people.

Maybe your band aimed for the moon, to be the next Beatles, but instead you’re still playing the open mic circuit in your 50’s. Maybe you had children so your children could have children but instead of being grandparents, you’re barren. Maybe you thought you were on track to be the next Iron Chef but instead you’re a pastrami pusher in the deli handed to you by Grandpa Bernie. Maybe you thought you were marrying up but in reality, you were abdicating your manhood, selling yourself short, teaching yourself and your children to stick out the misery instead of fighting for your happiness.

“I met a lot of dudes in prison that’s great people. There’s a lot of great people in prison. There’s a lot of talent going to waste. But yeah man! You have people in there with great minds, great hearts. They’re sincere people. They deserve second chances. A lot of them have 80 years or life without parole. Maybe they’ll never see the streets,” Kuntrell said. “But they deserve second chances.”

WHAT ABOUT THE VICTIM???? So sorry the man has to come up with $40 and report to a probation officer for blowing someone’s fucking head off. What about the brother,mother,father, sister and friends of the clerk that will never see him or her again. What about the fact that this person was just minding his own working hard and these 3 shitheads decided to kill the poor clerk and didn’t even take any money, they only killed her after she threatened to call the police and no one in their group of 3 ever tried to stop the robbery. Any of the 3 involved could have unloaded the gun before the robbery, argued to call it off, leave the scene and call the police, or about 10,000 other choices that would’ve prevented this horror.

Now that said he was only 14 and life imprisonment is cruel. But he definitely needed to do the 20 MINIMUM. At the end of the day the fact that he went away probably saved many other young men from following in his footsteps, yes DETERRENCE does work.

There are 4 reasons we lock people up. For the safety of society, to reform them, to punish them, and to deter others from committing crime

If there is another way, I’ll look at it and look hard. But you not ONCE mentioning the victim is truly disgusting and says a lot about you, you care more for violent criminals than victims.