Standing in front of her portrait, I missed the elegance of Michelle Obama. The weight of the loss was especially heavy as the night before, Stormy Daniels was interviewed about fucking Donald Trump.

I’m not calling him a name, as in Fucking Donald Trump. I’m talking about the act, as in she was fucking Donald Trump.

I don’t mind the drama of porn stars. Sex doesn’t scare me. But it’s out of context. There are too many people who can’t handle it and so there’s no room for antagonizing those in loveless marriages when you’re running a country founded by Puritans, especially when it turns out those Puritans are devout hypocrites.

I don’t mind the drama of porn stars. Sex doesn’t scare me. But it’s out of context. There are too many people who can’t handle it and so there’s no room for antagonizing those in loveless marriages when you’re running a country founded by Puritans, especially when it turns out those Puritans are devout hypocrites.

I had just come from the Museum of African American History and Culture. I tried getting tickets first thing in the morning. Tickets are available starting at 6:30AM. So I set my clock for 6:21AM. I made the miscalculation of reading the news for 9 minutes and by the time I looked up it was 6:40AM. When I logged onto the website, all of the time slots for the museum were sold out.

Like all things American, there’s a loophole. Turns out, you can get to the museum at 1:00PM to stand in line. I got there at 11:00AM. The woman ahead of me was talking to her daughter about Michelle Obama’s portrait. I was so taken with her excitement, I decided right then and there to make the National Portrait Gallery the final destination of my trip to Washington DC.

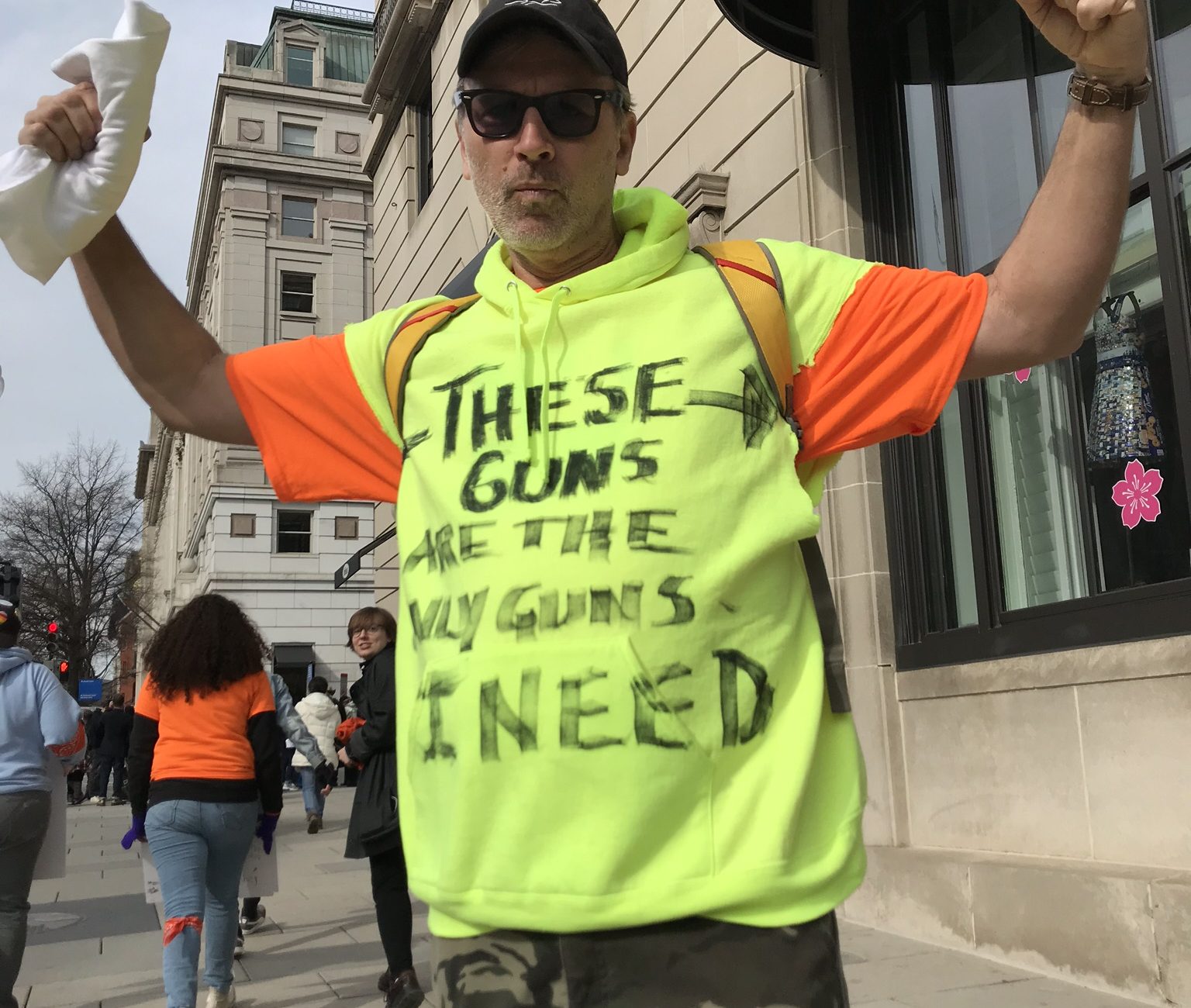

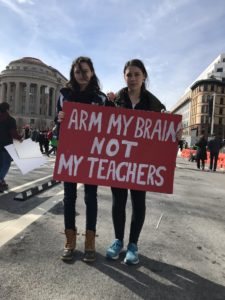

I went there to join the March For Our Lives.

I went there to join the March For Our Lives.

It was a pilgrimage, driving 12 hours from Chicago to Washington DC. To pass the time, I listened to a podcast called “Serial,” about a kid who spent the past 16 years in prison for the murder of his high school sweetheart. It was the perfect story to underscore the feeling of why I was making the journey. The more you listen, the more you become aware it’s impossible to hear about someone who’s been accused of something as if they’re innocent. Or to use fancy language, from the presumption of innocence. Guilt sticks. There are 12 episodes in the podcast. I listened to 6 on the way there and 6 on the way back.

In 1999, Adnan Syed was accused of strangling Hae Min Lee. The State maintains Adnan’s guilt despite Adnan maintaining his innocence.

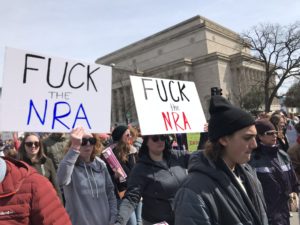

In 2018, there was a massacre in Parkland. The NRA maintains we have the right to shoot each other for sport despite high school students maintaining they have the right to go to school without the oppressive shadow of lockdown drills.

The kids from Parkland organized a march to protest gun violence. I don’t know who’s to blame. Is it The NRA? They turned the 2nd Amendment into scripture. Is it the gun lobbyists? They turned money into a weapon. Is it Bill Clinton? On his watch, the Assault Weapon Ban was allowed to lapse. Is it Laura Ingraham? She’s an actual grown up who plays a Fox News Bully on TV and just last week, she took the role too far when she taunted Daniel Hogg, an actual child who’s still actually going to Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, and having a hard time getting into the college of his choice. For fun, Laura Ingraham took a cheap shot at Daniel Hogg. Is she to blame? I don’t know. Who’s to blame? Is it us? If you’re not so sure, please allow me to sum it up for you in 2 word: Sandy Hook.

The kids from Parkland organized a march to protest gun violence. I don’t know who’s to blame. Is it The NRA? They turned the 2nd Amendment into scripture. Is it the gun lobbyists? They turned money into a weapon. Is it Bill Clinton? On his watch, the Assault Weapon Ban was allowed to lapse. Is it Laura Ingraham? She’s an actual grown up who plays a Fox News Bully on TV and just last week, she took the role too far when she taunted Daniel Hogg, an actual child who’s still actually going to Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, and having a hard time getting into the college of his choice. For fun, Laura Ingraham took a cheap shot at Daniel Hogg. Is she to blame? I don’t know. Who’s to blame? Is it us? If you’re not so sure, please allow me to sum it up for you in 2 word: Sandy Hook.

20 school children between the ages of 6 and 7 were murdered at an elementary school. What did we do? Nothing. You can only kick and scream for so long before you start sounding like Chicken Little, “The sky is falling! The sky is falling!” So what? We like it when the sky is falling. We’re a nation of Chicken Littles, Stormy Daniels & Podcast Villains. None of it’s seems real until it’s really you sitting behind prison walls for 16 years.

20 school children between the ages of 6 and 7 were murdered at an elementary school. What did we do? Nothing. You can only kick and scream for so long before you start sounding like Chicken Little, “The sky is falling! The sky is falling!” So what? We like it when the sky is falling. We’re a nation of Chicken Littles, Stormy Daniels & Podcast Villains. None of it’s seems real until it’s really you sitting behind prison walls for 16 years.

Adnan Syed adapted to a life in prison. But he adapted in the same way those of us who are living in the world of mass shootings have adapted. Most of the time we don’t talk about it. If you don’t talk about the prison walls it’s not prison, it’s life unfolding.

Call it what it is: a coping mechanism.

Just because we’ve learned how to quietly live in a world where shopping centers, movie theaters, high schools, elementary schools, nightclubs and churches have been turned into shooting ranges doesn’t mean we like it. But we’re resigned to the reality. That is to say, we’re resigned to the reality until someone comes along, asking questions.

Just because we’ve learned how to quietly live in a world where shopping centers, movie theaters, high schools, elementary schools, nightclubs and churches have been turned into shooting ranges doesn’t mean we like it. But we’re resigned to the reality. That is to say, we’re resigned to the reality until someone comes along, asking questions.

Sarah Koenig is a podcaster with questions who decided to take another look at the case against Adnan Syed. The kids from Parkland are survivors with questions who decided enough is enough. I’m a guy along for the ride who decided he wants to investigate why he’s repeating things in his writing. I’ve said this before and I’ll say it again, “The only thing those of us who survive a mass shooting can be sure of is that we’re sitting ducks.” It’s satisfying to say it. But nothing changes so then I have to ask myself if all I really want from this is another opportunity to be clever. Speaking of gallows humor, I saw Jordan Klepper at the March For Our Lives. He’s a comedian with a show on Comedy Central called “The Opposition.” He was interviewing people, mining the march for comedy gold.  At first, I was offended. Then I had to admit to myself I was jealous. He was there with a crew, shooting footage for a television show. I was there with an iPhone, taking pictures for my twitter feed. Who’s the joke? I realized we were both reacting and my instinct to judge his reaction is part of the problem. We’re too busy commenting on the reaction of other people instead of doing something meaningful to end the violence.

At first, I was offended. Then I had to admit to myself I was jealous. He was there with a crew, shooting footage for a television show. I was there with an iPhone, taking pictures for my twitter feed. Who’s the joke? I realized we were both reacting and my instinct to judge his reaction is part of the problem. We’re too busy commenting on the reaction of other people instead of doing something meaningful to end the violence.

A week ahead of the march in DC, I booked a room at Hotel Hive, a micro hotel around the corner from the Lincoln Memorial. In case you’re wondering what a micro hotel is, it’s a trendy hotel with trendy rooms. Typically, they have something pithy stenciled on the wall like, “And if the music is good you dance.”  I know it sounds ridiculous, but I like the feeling of walking into a room where the opulence has been replaced with graffiti. The bar is a local hang, which is also nice. I like sitting at a bar where the vibe is drunk locals and the commute home is a stumble to the elevator and 5 flights up.

I know it sounds ridiculous, but I like the feeling of walking into a room where the opulence has been replaced with graffiti. The bar is a local hang, which is also nice. I like sitting at a bar where the vibe is drunk locals and the commute home is a stumble to the elevator and 5 flights up.

I’m going to tell you a story about Blaine.

He was sitting next to me at the bar. We got to talking. He was from England. His travel time was the same duration as my travel time: 12 hours. He flew. I drove. He was on a pilgrimage, searching for answers still lingering from a vacation he took many years ago when he was shot. It took 48 surgeries and 13 years to fully recover. He sued England and won. His case was used to get guns off the streets. It wasn’t a school shooting or a civil rights movement or a march to save Blaine’s life, it was a simple lawsuit responsible for changing England, and it was the reason Blaine flew to America. He wanted to raise his profile. Walking along the route of the March For Our Lives, he managed to get himself interviewed by 5 different news outlets. When I met him at the bar, he was bragging to the bartender about his interviews.

I bought him a drink. I was curious. We got to talking about politics. Stormy Daniels was about to be interviewed by 60 Minutes. Everyone at the bar was talking about it even though the NCAA Tournament was still on. Blaine started going on and on in an English Accent about America. He told me Kamala Harris was the right person to run for vice president in the next election but he hadn’t settled on the right person for president. He asked what I thought about George Clooney. I told him Clooney was too selfish, too caught up in being famous. He’d cut a check for the kids from Parkland, but it was as big a sacrifice for him to cut a check as it was for me to buy a drink for Blaine.

I bought him a drink. I was curious. We got to talking about politics. Stormy Daniels was about to be interviewed by 60 Minutes. Everyone at the bar was talking about it even though the NCAA Tournament was still on. Blaine started going on and on in an English Accent about America. He told me Kamala Harris was the right person to run for vice president in the next election but he hadn’t settled on the right person for president. He asked what I thought about George Clooney. I told him Clooney was too selfish, too caught up in being famous. He’d cut a check for the kids from Parkland, but it was as big a sacrifice for him to cut a check as it was for me to buy a drink for Blaine.

“He’s too busy looking pretty in pictures with Amal,” I said.

“Who’s Amal?” he asked.

“His wife,” I said. “She’d be a great first lady. But she’s too qualified and if I had to guess, after watching how horribly Michelle Obama was treated, she has no interest in the abuse. Their life is too good. I will say George Clooney has the right skill set to beat Donald Trump. You cannot beat an entertainer with a politician.”

“His wife,” I said. “She’d be a great first lady. But she’s too qualified and if I had to guess, after watching how horribly Michelle Obama was treated, she has no interest in the abuse. Their life is too good. I will say George Clooney has the right skill set to beat Donald Trump. You cannot beat an entertainer with a politician.”

There it goes again, my habit of repeating myself, “You cannot beat an entertainer with a politician.” I like the way it sounds. It’s become my mantra and I don’t know what’s going on. Maybe it’s Post Traumatic Stress working its way through my consciousness or regret for my own anonymity despite a propensity for controversy.

Blaine bought everyone at the bar a shot of tequila. He’d been hitting on the girl to his right but I could see he really had eyes for the girl sitting on my left. Their combined age was 30. They were college girls but they looked like high school girls. Blaine was 49. I didn’t care. He was just blowing off steam, playing the role of big shot at the bar. We got into a conversation about a woman he’s in love with back in England. He’d just broken up with her. She was a pothead. The final straw came when he found himself smoking pot. He didn’t want to fall into the trap, so he broke things off until she came around.

“There is no going back,” I said. “She’s never coming around. You can’t change her. But if you’re having fun, then I vote for leaving her alone. Let her smoke pot until it’s not fun anymore for you to be around a pretty pothead. You don’t try to change people. That’s not what dating is about. You adore them until romance turns into nitpicking. Then you quietly excuse yourself from her life.”

“There is no going back,” I said. “She’s never coming around. You can’t change her. But if you’re having fun, then I vote for leaving her alone. Let her smoke pot until it’s not fun anymore for you to be around a pretty pothead. You don’t try to change people. That’s not what dating is about. You adore them until romance turns into nitpicking. Then you quietly excuse yourself from her life.”

“This was our second go at it,” he said. “We dated 5 years ago.”

“How old is she?” I asked.

“25,” he said.

“She doing exactly what she’s supposed to be doing at 25,” I said. “And you’re doing exactly what you’re supposed to be doing at 49. You’re talking all kinds of shit at a bar about a country you know nothing about since you don’t live here and you can’t solve the problem for us anymore than you can turn a pothead into a go-getter.”

“She doing exactly what she’s supposed to be doing at 25,” I said. “And you’re doing exactly what you’re supposed to be doing at 49. You’re talking all kinds of shit at a bar about a country you know nothing about since you don’t live here and you can’t solve the problem for us anymore than you can turn a pothead into a go-getter.”

“You’re a very negative person,” he said. “You don’t think George Clooney will run for president and you don’t think love will win the day.”

He didn’t say the second half of the sentence, “Love will win the day.” But I remember it that way since it makes Blaine out to be something he’s not, a guy who knows how to end his point on a button. He went on and on for hours, using his English Accent as a commodity, hitting on everyone at the bar, talking all kinds of shit, until the guy standing behind me at the bar finally leaned in and said, “This guy is a classic over talker!” It’s safe to say I liked everything about Blaine.  He lifted the room with his bullshit. Finally, as the hotel bar was getting ready to close for the night, he convinced one of the bartenders and a regular to go with him to another bar where they had better gin.

He lifted the room with his bullshit. Finally, as the hotel bar was getting ready to close for the night, he convinced one of the bartenders and a regular to go with him to another bar where they had better gin.

“The gin here is crap,” he protested, sounding impressive with an English Accent.

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the regular who was thinking about going with Blaine to the next bar talking it over with the girl at the front desk. A few minutes later, she walked back over to the bar.

“I can’t go with you for another drink,” she said. “I don’t know you and it doesn’t feel right.”

“That’s the best decision you’ve made all night,” Blaine said.

As he finished his drink and put on his jacket, I asked if I could interview him.

As he finished his drink and put on his jacket, I asked if I could interview him.

“Greg from Max’s Deli wants to interview me,” he said. “Why? What on earth could that possibly accomplish?”

“You came to the march to raise your profile,” I said. “I think I can help. But it’s up to you. I don’t ask twice.”

“I have meetings all afternoon,” he said. “We could meet beforehand. I’ll be downstairs having breakfast at 8:30AM.”

We made a plan to meet at the bar for breakfast. Then Blaine went out into the night chasing better gin and I stumbled to the elevator for my 5 flight commute.

The next morning I got up at 5AM. I was excited. I went downstairs and parked myself at a table. I tried getting tickets to the African American Museum. I had a cup of coffee and sorted through my pictures of the march, posting on my twitter feed, grumbling about Jordan Klepper.  It’s the new national pastime, comparing yourself to other people. A few hours later, I saw Blaine.

It’s the new national pastime, comparing yourself to other people. A few hours later, I saw Blaine.

“So I want to interview you,” I began.

“I need to know more about you first,” he cut me off. His tone was hostile. I couldn’t tell if he was hung over or if something else was bothering him.

“I need to know what it’s for, where it’s going, what it’s doing because I have to watch my public profile because I do some things publicly so you need to…you need to tell me,” he said. “Um, what’s the website? We need to have a professional conversation. What’s the purpose? What do you do? I don’t even know what you do for a living. You said you own a deli.”

For those of you reading who don’t know, I’m going to take you through the Cliff Notes of what you’d find if you googled “Greg from Max’s Deli.”

I told him about Max’s Deli, about being a Jewish Man running a Jewish Deli who’s in love with a Jewish Woman. I told him about the reaction I had after the murder in Charlottesville, when the president said both sides were to blame. I asked him if both sides were to blame in 1943 when the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto rose up against the Nazis.

I told him about Max’s Deli, about being a Jewish Man running a Jewish Deli who’s in love with a Jewish Woman. I told him about the reaction I had after the murder in Charlottesville, when the president said both sides were to blame. I asked him if both sides were to blame in 1943 when the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto rose up against the Nazis.

“Of course not,” he said.

I showed him the ad I made for Rosh Hashanah, the season of atonement, encouraging Donald Trump to own his mistake and make it right. I told him about the backlash, my first brush with going viral.

Then I told him about the shooting in Las Vegas.

“I know about Las Vegas,” he said. “59 killed. 527 injured.”

He was offended that I thought he didn’t know. I told him I was sorry but I was unaware of what was going on in England and so I didn’t think someone from England would know everything going on in America. I explained to him the tweet written by Ava DuVernay on the morning news broke of the Las Vegas Shooting. She asked why a white shooter is called a lone wolf but a brown shooter or a black shooter is called a terrorist. I told him about my attempt to answer the question with a retweet: “When I heard there was a shooting at a country western concert and the shooter was white I felt relief, white people shooting white people isn’t terrorism, white people shooting white people is community outreach.”

He was offended that I thought he didn’t know. I told him I was sorry but I was unaware of what was going on in England and so I didn’t think someone from England would know everything going on in America. I explained to him the tweet written by Ava DuVernay on the morning news broke of the Las Vegas Shooting. She asked why a white shooter is called a lone wolf but a brown shooter or a black shooter is called a terrorist. I told him about my attempt to answer the question with a retweet: “When I heard there was a shooting at a country western concert and the shooter was white I felt relief, white people shooting white people isn’t terrorism, white people shooting white people is community outreach.”

I don’t like doing this. I don’t like talking about myself. It wasn’t the point of why we were meeting in the earliest hours of Blaine’s hangover. It felt like a soliloquy. But when he asked, there was something hostile in his tone. His attitude was dismissive. I was trying to get underneath a feeling he was flinging in my direction. In the same way I’m not afraid of porn stars and sex it’s also safe to say I’m not afraid of British Bullies and emotion.

“Well I googled you this morning, um, so I’m glad you’ve had full disclosure, because I found out all about that anyway and the tweet and everything like that. Um, for me it’s a little bit too controversial, um, to do this because I’m building my profile here. I have a small profile in the UK and I’m building it here. And, and…controversy can be an instant suicide for something like this. Um I have to build myself as a neutral in the process and, um, I think you’re controversial and I don’t want to be controversial until I have a profile that’s big enough to handle being controversial and not be shot down in flames.”

“Well I googled you this morning, um, so I’m glad you’ve had full disclosure, because I found out all about that anyway and the tweet and everything like that. Um, for me it’s a little bit too controversial, um, to do this because I’m building my profile here. I have a small profile in the UK and I’m building it here. And, and…controversy can be an instant suicide for something like this. Um I have to build myself as a neutral in the process and, um, I think you’re controversial and I don’t want to be controversial until I have a profile that’s big enough to handle being controversial and not be shot down in flames.”

“Cool,” I said. “Okay.”

“So I did mean it last night. Um, and I did remember it. And even when I’m drunk I’ve got quite a good radar. Um, so I did mean it. But I wasn’t aware exactly what you’re doing but I see some controversy in you and I think that works for you but it doesn’t work for me,” he said.

I didn’t say anything. I was stewing, furious. I left the silence hanging there. I was no longer interested in playing nursemaid to Blaine’s fragile emotions.

“Professional discussion,” he said to fill the silence.

“Professional discussion,” he said to fill the silence.

“I’m not sure what you mean,” I said, lying.

“We’re having a professional discussion rather than just being friends sort of talking,” he said.

“I don’t think we’re having a professional conversation,” I shot back quickly. “I think you’re backing out of something cuz you’re nervous.”

“No, no, no!” he said. “I’m not nervous.”

“You’re nervous,” I said. “I think you’re pussying out.”

“That’s kind of exactly why I don’t want to do it,” he said.

“Well then enjoy your anonymity. You’re never going to lift your profile in this country if you’re afraid of controversy. People are fucking dying. We don’t have time for this coy, calculated, long game you’re playing. Last night you said it was going to take 50 years to make this change happen but those kids on the National Mall, those teenagers, you think they have time? They have dead fucking friends. You think 140 characters matter. You think my tweet matters? It doesn’t matter,” I said. “It doesn’t matter!”

“Well then enjoy your anonymity. You’re never going to lift your profile in this country if you’re afraid of controversy. People are fucking dying. We don’t have time for this coy, calculated, long game you’re playing. Last night you said it was going to take 50 years to make this change happen but those kids on the National Mall, those teenagers, you think they have time? They have dead fucking friends. You think 140 characters matter. You think my tweet matters? It doesn’t matter,” I said. “It doesn’t matter!”

“Greg I understand. Greg I understand. Greg!” he said. “I understand. I’m sitting here. I’ve got a meeting to go to now. And then I’ve got to prepare myself for my flight, my night flight. I don’t want to get into a heated discussion.”

“Adios,” I said. “Adios.”

At this point, I should reveal something, Emily Anne was sitting at the table. We took the trip together. Emily Anne is a teacher. This is her spring break. But instead of chasing fun on the beaches of Florida, I took her to Washington DC to chase justice. The night before, she’d been sitting between me and Blaine. At this point, I should also reveal when Blaine bought everyone a shot of tequila, I offered my shot to the blond girl sitting to my left. When she turned it down, I poured the shot in the metal shelf where bartenders pour booze to allow for spillage. Then I faked a face.

At this point, I should reveal something, Emily Anne was sitting at the table. We took the trip together. Emily Anne is a teacher. This is her spring break. But instead of chasing fun on the beaches of Florida, I took her to Washington DC to chase justice. The night before, she’d been sitting between me and Blaine. At this point, I should also reveal when Blaine bought everyone a shot of tequila, I offered my shot to the blond girl sitting to my left. When she turned it down, I poured the shot in the metal shelf where bartenders pour booze to allow for spillage. Then I faked a face.

“Awful,” I said. “Tastes like anger.”

Before I continue the conversation with Blaine, I think this is a good point in this story to talk about returning to the presumption of innocence, something I’ve been chasing since a retweet turned me into an outlaw. I think this is why I was so taken with “Serial,” the podcast about Adnan Syed. I kept giving Adnan the benefit of the doubt. But if I was honest, I never fully believed he was innocent. Imagine if he is innocent, how infuriating it must be. I get it. The only thing I’m guilty of is reacting. But here I was, almost 7 months later, trying to have a conversation where I could learn something about ending the epidemic of gun violence, and Blaine was coming at me like I was seeking out controversy. I wasn’t. I was hoping to ask questions.

Before I continue the conversation with Blaine, I think this is a good point in this story to talk about returning to the presumption of innocence, something I’ve been chasing since a retweet turned me into an outlaw. I think this is why I was so taken with “Serial,” the podcast about Adnan Syed. I kept giving Adnan the benefit of the doubt. But if I was honest, I never fully believed he was innocent. Imagine if he is innocent, how infuriating it must be. I get it. The only thing I’m guilty of is reacting. But here I was, almost 7 months later, trying to have a conversation where I could learn something about ending the epidemic of gun violence, and Blaine was coming at me like I was seeking out controversy. I wasn’t. I was hoping to ask questions.

“Do you have a view on this, Emily?” he asked.

“Um, I understand what you’re saying. You have to…if you’re trying to build something…you have to…this is what…social media can be very powerful but it also can be really dangerous so you need to know who you’re talking to. Just like last night when he asked you about his website and you said you have to look at it first. Well he has to know who he’s talking to first before he posts something. He hasn’t had a lot of time to do that,” she said.

“Um, I understand what you’re saying. You have to…if you’re trying to build something…you have to…this is what…social media can be very powerful but it also can be really dangerous so you need to know who you’re talking to. Just like last night when he asked you about his website and you said you have to look at it first. Well he has to know who he’s talking to first before he posts something. He hasn’t had a lot of time to do that,” she said.

I need to address what Emily is talking about. Last night, sitting at the bar, Blaine showed me his website. He asked me what I thought. I told him it looked fine. I told him I don’t give out free advice. The last thing I said was a joke. But it’s true, since Grandpa Bernie always said, “Free advice is worth exactly what you paid for it.” Truth be told, I liked the website. It was simple. It didn’t need to be filled with words and explanations and statistics and credentials. If someone wants to reach out, that’s really all his website was about, creating enough interest to take the next step and I was already living in the next step, playing along at the bar, having a heated conversation. The idea Blaine was suddenly adverse to having a heated conversation based on what he read about me was infuriating in the way only an innocent man can know how it feels to be judged.

“So you’re a school teacher?” Blaine said.

“So you’re a school teacher?” Blaine said.

“Yeah,” Emily said.

“Ok,” he said. “So I think I remember that from last night. And, um, what age of the kids do you teach?”

“3rd grade,” she said.

“3rd grade,” he said. “So that’s like 8 years old? Or something like that?”

He was buying time, repeating exactly what Emily said to buy time. He was using Emily to take the focus off the focus. I know the trick. I know the game. Blaine is an addict, hooked on self importance. So as a fellow addict, hooked on the equation of comedy equals tragedy plus time, I did what I’m trained to do: don’t solve the problem, make the problem worse. I sat there quietly, listening to them, feeling myself pull away, from Blaine, from Emily.

“Ok,” he said. “Do you like that?”

“Yes,” she said.

They were done. They both looked at me. I had nothing to say. I didn’t want to talk to him. I didn’t want to talk to her. I sat there, taking in their judgment.

They were done. They both looked at me. I had nothing to say. I didn’t want to talk to him. I didn’t want to talk to her. I sat there, taking in their judgment.

“Well, um,” he finally said to break the silence. “I’m gonna go and, um, finish my breakfast. It’s been great to meet you. Shake hands?”

I shook his hand. It’s the only thing I regret. Blaine is a coward. Cowardice is contagious, it’s transmitted when you look a coward in the eye and shake his fucking hand.

“Bye Emily,” he said.

“Nice meeting you,” she said.

“And you,” he said.

Blaine got up. He left his garbage on the table. Both his metaphorical garbage and his actual garbage, which I bussed for him so no one else would have to clean up his mess. The night before, after playing big shot at the bar, buying everyone shots and talking all kinds of shit, when he paid his tab, Blaine stiffed the bartender. Luckily, the bartender was friends with the regular Blaine was petitioning to go drinking with him, and she was able to shame him into reaching into his pocket for $20 bucks. He protested.

Blaine got up. He left his garbage on the table. Both his metaphorical garbage and his actual garbage, which I bussed for him so no one else would have to clean up his mess. The night before, after playing big shot at the bar, buying everyone shots and talking all kinds of shit, when he paid his tab, Blaine stiffed the bartender. Luckily, the bartender was friends with the regular Blaine was petitioning to go drinking with him, and she was able to shame him into reaching into his pocket for $20 bucks. He protested.

“Why should I?” he moaned. “Where are they now?”

They were cleaning up the bar, getting ready to go home, counting on him to help them make a little bit of money so their night wasn’t a total bust. I knew Blaine was crap, like the gin. But I’m a fan of imperfect messengers, which is why I got my ass out of bed at 5AM to ask questions.

They were cleaning up the bar, getting ready to go home, counting on him to help them make a little bit of money so their night wasn’t a total bust. I knew Blaine was crap, like the gin. But I’m a fan of imperfect messengers, which is why I got my ass out of bed at 5AM to ask questions.

And listen.

I marched up the stairs to my room, 5 flights. Emily followed me. She asked if I wanted to get breakfast. I told her I wasn’t hungry, I’d lost my appetite. I packed up my things and told her I was going for a walk.

I walked blindly, talking to myself like a madman, processing the humiliation. When you’re walking the streets of a new city, you’re orbiting the places you know. The night before, we stopped by the Lincoln Memorial. Without knowing it, I was making my way back so I could turn off the war in my brain with the words from Lincoln’s second inaugural address, which are carved into the wall across from the Gettysburg Address.

The Gettysburg Address is about leading with the good news and the power of saying more with less. Lincoln’s second inaugural address is about slavery, the lies we tell ourselves to justify slavery. “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.”

The Gettysburg Address is about leading with the good news and the power of saying more with less. Lincoln’s second inaugural address is about slavery, the lies we tell ourselves to justify slavery. “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.”

I kept reading the words, over and over, taking in the lies I’d been told, how the Civil War was about preserving the union, when there it was, in the second inaugural address, carved into the wall, the reason for the conflict, slavery. Woe unto the world for the offense of slavery. But there was a price to be paid, “Every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword.” Woe unto the world for the offense of guns. But there is a price to be paid. Every drop of blood paid for with a loan from The NRA shall tarnish your manhood three-fold plus the smear of Blaine’s bullshit.

He was the messenger. I was the scribe. Just as no good deed goes unpunished, no pilgrimage comes without blisters on your pride. I sat on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, listening to a marching band, holding my head in my hands, lost in thought, lost in emotion. I made my way to the African American Museum, where I stood in line and eavesdropped, deciding I’d end my pilgrimage at the National Portrait Gallery. Standing in front of Michelle Obama’s portrait, I asked how she did it, how she endured so much abuse, how she took so many blows to her pride and yet came out on the other side with enough grace for all of us to share.

He was the messenger. I was the scribe. Just as no good deed goes unpunished, no pilgrimage comes without blisters on your pride. I sat on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, listening to a marching band, holding my head in my hands, lost in thought, lost in emotion. I made my way to the African American Museum, where I stood in line and eavesdropped, deciding I’d end my pilgrimage at the National Portrait Gallery. Standing in front of Michelle Obama’s portrait, I asked how she did it, how she endured so much abuse, how she took so many blows to her pride and yet came out on the other side with enough grace for all of us to share.

She didn’t answer. Neither did Lincoln. Paintings and statues can’t talk. Or maybe they can and that was their answer. They don’t know how they did what they did, they just did what they did and all the rest of it is the conversation we’re having to fill the time on the long march back to the presumption of innocence, something we never truly get back.

She didn’t answer. Neither did Lincoln. Paintings and statues can’t talk. Or maybe they can and that was their answer. They don’t know how they did what they did, they just did what they did and all the rest of it is the conversation we’re having to fill the time on the long march back to the presumption of innocence, something we never truly get back.